Making a documentary is like climbing Everest. Go in without the right mindset, and you’ll most likely exhaust yourself midway. This is because in addition to demanding the usual filmmaking flair—creativity, managing multiple aspects of filmmaking, and having an eye for detail—you also need to have impeccable research skills to create one that is worth watching.

So if you thought you could go out with a camera, shoot some footage, and call it a documentary, you're in for a rude awakening. It is a process that often takes weeks and months to come to fruition. However, you can make this process easier by choosing the right people and tools to work with. For instance, if you aren’t a video editing expert, doing a quick course on editing and picking a user-friendly editor with a good feature portfolio will make life much easier.

But even with the right editor, you still need to know how to approach documentary filmmaking and what skillset you need to develop in order to create a successful project. And that is exactly what we'll cover in this article. We'll show everything you need to know to create a documentary from start to finish:

- What is a Documentary

- Types of Documentaries

- Step 1: Planning and Pre-Production

- Step 2: Production and Shooting

- Step 3: Editing and Post-Production

- Step 4: Distributing the Documentary

Let's get started

What is a Documentary?

'Documentary' is a term used to refer to non-fiction movies that try to serve as a document of ground reality. Often, they take a unique or inspiring take on a previously explored idea. A lot of documentaries are made by people who believe that a particular area or point of view hasn’t been appropriately or sufficiently covered by the media in general.

However, even businesses can use documentaries to subtly market their concept and show their target audience the use cases your product or service has. For instance, here’s the trailer of a documentary cattle rearing for slaughter produced by MailChimp Presents, which aims at creating original content aimed at small business owners. .

Pro Tip: Creating trailers is essential to promoting your documentary across multiple social media platforms. It gives the audience a glimpse of what is to come, which is why you need to focus on the editing of your trailer just as much as you focus on the editing of the actual documentary. Thankfully, you can do this quite quickly and easily by signing up for a free account on InVideo and using one of their customized trailer templates.

Before we talk about how to make a documentary, you should determine the type of documentary you want to make. Let’s talk about your options when it comes to the types you can choose from.

Types of Documentaries

While in their most basic form, documentaries are non-fictional, there are several types of documentary genres. Before we talk about how to make a documentary, you should determine the type of documentary you want to create.

If you’re wondering which type will best suit you, that answer depends on several factors like the subject you want to discuss, the approach you want to take, and whether you’ll participate in the documentary yourself.

We discuss 6 types of documentaries below as proposed by Bill Nichols, an American film critic, so you can learn about the options you have and pick a type that fits your style or aligns with the subject of your documentary.

1. Poetic Documentaries

Poetic documentaries focus on showing the world to the viewers through a creative and often emotional point of view. They’re abstract, don’t follow a linear narrative, and are typically experimental in terms of the content. Their objective is to invoke an emotion in the viewers rather than make a case about something.

For instance, Rain, a short 1929-poetic documentary by Joris Ivans is a compilation of images that helps you experience how it would feel to be in an Amsterdam rainstorm.

You will notice how the choice of music is essential to poetic documentaries because sound is one of the primary ways of depicting emotion in film. If you’re making short documentaries, you can find a wide selection of royalty-free music tracks that you can use with InVideo’s stock music library.

2. Expository Documentaries

Most documentaries that you see are expository documentaries; they’re usually aimed at either informing or persuading viewers with a “Voice of God” narration. Expository documentaries don’t leave much room for subjectivity; it clearly makes a viewer feel a certain way by making evidence-backed arguments. Here’s an example of an expository document:

If you want to create a documentary in its simplest form and be direct about your story, you should consider making an expository documentary because it gives you a lot more creative control over the narration than other types.

3. Observational Documentaries

Observational documentaries are documentaries where the creator makes a point or several points by showing footage that conveys reality.

The observational style of documentaries became common after the 60s when camera equipment evolved and became more portable. These tend to be much less directed than expository documentaries, and often try to table several points of view through raw, and sometimes previously unseen footage.

Crisis: Behind a Presidential Committee is an excellent example, as is Coldplay’s A Head Full of Dreams. Both of these followed the lives of important public figures through clips and recordings taken at different parts of their journey.

4. Participatory Documentaries

Participatory documentaries are one of the most natural styles for beginners. The creator of the documentary usually gets involved in the film’s narrative when creating participatory documentaries.

The extent of participation could range from just lending the voice to directly influencing the narrative by being in the film. Therefore, some people believe that in principle, all documentaries are participatory because we don’t have any standard participation threshold to differentiate it from other types of documentaries.

Roger & Me is a great example of a participatory documentary where Michael Moore himself conducts interviews about how GM’s decision to close auto plants in Flint, Michigan, had dire economic consequences. He weaves the storyline around his personal experiences as someone who was brought up in Flint.

5. Reflexive Documentaries

Reflexive documentaries are an extreme form of participatory documentaries in that they solely focus on the documentary’s creator.

No external subject is explored in a reflexive documentary, but it does reveal the process of creating the film. The cinematographer also includes behind-the-scenes footage, including the production journey, interviews, and editing in a reflexive documentary.

The most cited example of a reflexive documentary is Man with a Camera, a silent documentary from 1929 that has no story and no actors. It was created by the Soviet-Russian director Dziga Vertov and highlights the ordinary Soviet life of the 1920s.

6. Performative Documentaries

Performative documentaries work like a bridge between the creator’s personal experiences and a larger subject area like politics or history. They’re a combination of multiple styles and aim to share the creator’s point of view with the audience. Performative documentaries often include footage of the production process and other clips that may help establish the creator’s relationship with the subject.

Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 is an excellent example of a performative documentary. Michael himself appears in the documentary asking questions to subjects and shares his understanding of the events of the Iraq war and how the U.S. responded to it. The trailer here provides a glimpse of the storyline as well as the kind of clips he has used to make a compelling case for his POV.

You will notice the choice of music makes this trailer so much more interesting to watch. To get a better understanding of how to add music to your videos to increase engagement, check out this blog.

Now that you understand what are the different types of documentaries, you’ll need to create a roadmap and iron out some pre-production particulars before you can finally turn the camera on and begin filming.

Step 1: Planning and Pre-Production

A lot more goes into a documentary as compared to a typical film – where you have control over most external and internal factors. While making a documentary, you’ll still need technical knowledge of filmmaking and a creator’s eye, but since it is based on true events, you will also need to factor in unprecedented occurrences and be willing to work around a schedule.

Thankfully, there are a few skills and lessons that can make it slightly easier to create a documentary film. You will need to commit to learning the process so that you can ensure fewer hiccups while actually filming and editing. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how you can create a plan for your documentary before you start filming.

1. Research

The first step of the planning process is research. Before you even begin gathering material, you will have to get a fair understanding of the subject you are making a documentary on. You need a ton of information so you can determine what footage will be relevant and how to film it.

This means reading up and gathering as much factual information as possible and then gathering historical clips and images that tie in with your narrative.

Plus, there can potentially be several other documentaries out there that talk about the same subject. So, why will someone want to watch your documentary? For this, you need a unique angle for your documentary that talks about the subject differently, or in a better way.

Start your research with archival materials such as newspapers, old clips, academic research papers, images, governmental documents, letters and journals, and credible articles on the internet.

Once you’ve got some primary research as groundwork, pick up each piece of your research and dig deeper. Also, create a list of experts that you can interview for your documentary. You can reach out to academics and research authorities for helping you gain a more refined insight into an event. If your documentary is about a relatively recent historical event, you might be able to find primary witnesses. They’ll be able to give you a first-hand description of the event and help you with research.

Here’s a quick tutorial that gives you a good overview of what documentary research involves:

2. Creating the story outline

Once you’ve done your research, you need a skeleton for your documentary. You need to put the pieces of research into a coherent outline so it effectively communicates the message to the audience. You might not need to think a lot about the structure if your documentary is about a historical event because you’ll need to use chronological order.

However, in other cases, you can use the following three-act structure for creating your storyline:

Act One: Inciting Incident — This is where you lay the groundwork and present the inciting incident that marks the beginning of your story.

Act Two: Character Arc — This is the part where the characters start experiencing a change because of what’s happening in your story.

Act Three: Climax — This is where your characters find a resolution to the story’s central problem and wrap up the story.

This is also a structure that fiction films follow. However, with a documentary, you’ll have several other things to include in your storyline including narration, voice-overs, interviews, talking head shots, and B-roll.

You won’t have these assets just yet, but be mindful of them as you create your story outline. Once you have your outline, it’s time to set up interviews.

3. Setting up interviews

Interviews are an exciting part of the process of learning how to make a documentary. They’re an important pillar of your documentary and will greatly influence the end result. For this reason, you need to make your interviews compelling and scrupulous.

In some cases, you might not have a lot of choices in how you get in touch if you only have their phone number. However, e-mail should be your first choice if available. Be sure to include the details of your documentary, the reason you’re making the documentary, and how their role fits in the documentary.

If they don’t respond, a follow-up email is okay, but don’t push if you don’t hear back after a follow up. If they do respond, send an email asking about their availability. When arranging a time slot with the subject, be sure to ask for a little more time than you believe you need.

If the subject agrees and the subject’s residence or office isn’t important to the story, ask them if they’d be willing to come to a place where your camera setup already exists. However, don’t insist on it if they say they’d prefer you bring the setup and crew over to a place of their choice.

4. Assembling your gear

While learning how to make a documentary, it’s important to talk about what equipment you’ll need so you can get some practice beforehand with handling them.

Assembling your gear is the final step before you can finally start filming. There’s no one-size-fits-all list of equipment you can use. It can be as simple or complex as you want. You can even use your phone to shoot footage in some cases. Here’s a blog detailing the full list of equipment you can have for your project.

However, here’s the bare minimum that you’ll need:

- Camera: This can be your phone, but a camera that allows you to change lenses and fine-tune advanced settings is ideal. If you’re looking for a decent camera, the Fujifilm X-T4 is an excellent choice.

- Microphone: You will need two different sets of microphones – one to record audio while you’re filming on the move and one to record voice-overs for the narrated part of the documentary. For recording your voice-over online, you can take the help of an editor like InVideo that allows you to do this within the editor itself.

The Sennheiser Pro Audio XSW-D Portable Lavalier set is a great, not-so-expensive choice and comes with almost all the accessories you’ll need to get started.

- Tripod or gimbal: Using camera support produces professional, non-shaky footage. If you get a tripod, be sure to get one with a video head. The Manfrotto MVH502A is an excellent choice if you want a tripod. Alternatively, if you’re looking for a gimbal, consider the DJI RSC 2.

While this is the bare minimum, that’s not the benchmark you should aim for. You should also get all pieces of equipment you can from the following list:

- XLR audio adapters: If you’re using a professional camera and a lavalier or boom microphone, you’ll need an XLR adapter. Make sure that the adapter is mountable to the camera and tripod so it’s convenient—BeachTek DXA-HDV High-Performance Camcorder Adapter is a great option that mounts onto both your camera and the tripod. This isn’t something you need if you’re using a DSLR camera and a DSLR-compatible lavalier mic though.

- Boom pole: You’ll need a boom pole to pick up good quality sound from people who aren’t wearing a lavalier mic. You might consider Rode Boompole Pro. It’s lightweight and extends up to 3M - which is ample in most cases.

- Reflectors and lights: If you’re shooting outdoors, you don’t need to carry lights. Just use the natural light and place reflectors to add even more light and even out the shadows.

However, when you’re shooting indoors, say for an interview, you’ll need a lighting kit. Shooting indoors without proper lighting will produce poor quality footage, so it’s best not to skip the lighting kit. You can get a Neewer 2 Packs Advanced 2.4G 660 lighting kit if you don’t want to overspend on a lighting kit.

- Memory cards and batteries: Always carry a lot more memory cards and batteries than you think you need. You’ll thank yourself later. Consider getting the Lexar Professional 1667x SXDC UHS-II card. They’re not very expensive, but you might be able to get a UHS-I card for cheaper if you’re working with a budget.

- RAID system: Storing the raw footage just on your computer is suicide. Back it up on multiple external disks so you can recover the footage if something goes wrong with the computer. SanDisk Professional G-RAID 2 comes with dual Thunderbolt 3 ports, daisy-chaining for 5 additional devices, and a 5-year warranty—a great choice if you don’t mind the price.

- Bags and cases: Bags and cases will make carrying your equipment a lot easier. They can get slightly expensive, but if you have the budget, definitely consider investing in them. Pelican 1510M Mobility Case can be a good choice for putting your gear into while you’re on the move.

Once you’ve got your gear sorted out, you can start taking the first steps towards actual production.

Step 2: Production and Shooting

You can now get started with the exciting part—the production and shooting. Following are the things you need to be mindful of during production.

1. Putting together a small crew

Creating a documentary is often a long and tiring process. And while it’s not entirely impossible to create a documentary without a crew, like Márcio describes in this video below, it is a lot more work than is required.

Even if you’re producing a small documentary, it’s always great to have at least a few crew members with skill sets that complement yours so that you can create a stellar project. The more aspects of production that you can delegate to crew members, the easier it will be for you to manage and bring the documentary to life. .

However, if your budget does not allow hiring a big team, you can also work with freelancers. Start by identifying things you can do yourself and things you’ll need help in. Here are a few roles you can outsource:

- Producer or Director: In many cases, you’ll be able to act as the Director yourself. However, if you’d like to focus on a different area of the documentary, you can hire a Producer or Director for coordinating the shoots, interviewing subjects, and managing the team.

- Scriptwriter: Your scriptwriter will construct your story by writing the narration for your documentary or coherently lining up the interviews. Script is a key element of your documentary, so you need someone who knows how to create a compelling script that will hook your audience.

- Cinematographer: You need someone to lead the camera. The cinematographer will help ensure that the footage is recorded professionally. The person will be in charge of monitoring the video, sound, and light. In some cases, though, sound and light are handled by a different person who specializes in that area.

- Editor: The editor is responsible your bringing your documentary to life, for giving voice to your narrative. Depending on your own skillset as a filmmaker, you may want to outsource a part of the editing or animation process. If you’re doing it yourself, you can take the help of an online video editing tool like InVideo that allows you to create compelling videos in minutes.

Once you’ve got a crew to make things happen and get things rolling, you can start shooting.

2. Record more footage than you think is required

Unlike in films, when you’re making documentaries, you mostly cannot have a do-over if you didn’t film something the first time around. It is therefore a good idea to record more than your narration or script requires. Film in various different camera shots and angles.

This does two things – it allows you to have footage of something that might not have been obvious at the time of scripting and it gives your editors the flexibility to choose from several shots so they can pick the best one. If you have some experience and know exactly what shots you want, you’ll be able to list them. But if you don’t, just focus on collecting as many shots as you can. This also includes B-roll—collect as much of it as you can.

Following are some types of shots that you might need to take:

- Talking head shots: These are shots of people—you, the cameraman, or the subjects—talking to the camera.

- A-roll: A-roll is the central, most important footage you’ve collected for your documentary. This can include the footage of the event, interviews, and everything else that’s essential to your documentary’s core idea.

- B-roll: B-roll is the transitionary footage that adds context to your documentary.

- Animation: Animations are your backups. Often, there might be shots or footage you couldn’t take. When that happens, you can supplement your narration with animated shots. You can also add animations to the intro to make it more attractive.

3. Shooting interviews

You’ll have scheduled interviews beforehand, so reach for the interview before time to get everything set up. While your crew gets everything ready, take some time to have a chat with your subject. This will help break the ice, make them more comfortable, and help you understand their side of the story.

You’ll also need to get the setting in order. If it’s an indoor interview, you’ll need to determine an appropriate background and use a three-point light setup to make the video look well-lit. Once you’ve done that, you can decide on where you’ll place the camera.

If it’s a sit-down interview, the subject should face the interviewer and place the camera such that it faces perpendicular to the interviewer’s eyeline.

Start the interview with general, open-ended questions. It’s also important to be flexible. Don’t keep the interview restricted if the subject wants to talk about something other than the core topic. If the subject isn’t comfortable answering a question, gracefully move on to the next one. Always remember to steer clear of yes or no questions. Your aim is to get answers that speak to the topic at length.

Here’s an excellent video where Mark Bone speaks on how you can get deeper responses from your subject:

Once the subject starts talking, don’t interrupt. If you believe the interview is going on a major tangent from the storyline, let the subject complete a sentence and use body language to convey that it’s time for the next question. For instance, one the subject completes a sentence, they break eye contact. Then, use the next question to subtly bring the subject back to the storyline. If you have more than you need, you can always trim and cut your clips during the editing process and you can easily use InVideo’s online editor for this.

4. Organizing and storing footage on the go

You’ll be recording an overwhelming volume of footage when you shoot for a documentary. If you don’t organize it on the go, you’ll overwhelm yourself later, or worse yet, lose some of that footage. This is why it’s always best to upload and organize your footage and back it up immediately after shootings.

Start by arranging the files in appropriate folders so it’s easier to track a piece of footage when you need it. As a rule of thumb, always keep your B-roll separate from your interviews. Separate them by creating different bins and prioritize them on the basis of how frequently you use them.

Finally, create a “best-footage” box where you’ll put the best shots in your footage. Doing this will make it easier to directly access footage that you’ll most likely use in the documentary, without having to skim through a ton of other footage.

Hear from a video editor himself how he organizes his footage:

Step 3: Editing and Post-Production

So, you’ve got all the footage you need at this point. It’s time to head back indoors and start post-production and editing the footage. There are several things you need to do at the post-production stage as discussed below.

1. Writing a script

You can now pick up your storyline again and use it as you write a script for the documentary. Writing the script can feel like a big jigsaw puzzle at first. But as you start putting the pieces in the right places, you’ll notice the big picture revealing itself.

When writing a script, you should follow some fundamental principles. For instance, you should always give your documentary a strong start that puts the core message forward. This could be an incident that’s controversial or gets people to think about something. Following the incident, set up a compelling portion for communicating the core problem such that it provokes the audience to ask why something is happening.

As you transition to the body of the documentary, you might start feeling a little lost with a giant volume of footage. However, as you go, just ensure that the scene or footage you add moves the story forward and takes the audience a step closer to the end. If it doesn’t, skip it—don’t get attached to a scene you love; you can always add some “uncut footage” at the end.

Watch Julia Ward, a writing and directing consultant, in action as she explains how you can go about writing your script:

Remember, your script isn’t written in stone. What looks terrific on paper might not manifest that well on the screen. If that happens, you can always make changes along the way. But it is good to have a starting point because otherwise, it can get too overwhelming.

2. Making a rough cut

At this point, you can sit in front of a screen and start working on a rough cut. You don’t need to add visual effects or music to the footage just yet, but at this point, you’ll have the documentary’s narrative in place.

Since the rough cut is only the first round of editing, your footage will still be much larger than the final product. If there’s a scene that you’re not sure about, you can just leave it in for now, and remove it later.

Essentially, you need to piece the footage you want in the documentary together when you work on the rough cut, but of course, you can add or remove scenes at a later stage. Don’t be in a rush to finish your rough cut though. Based on the volume of footage, the number of hours you put in, and other factors, finishing the rough cut can take you months.

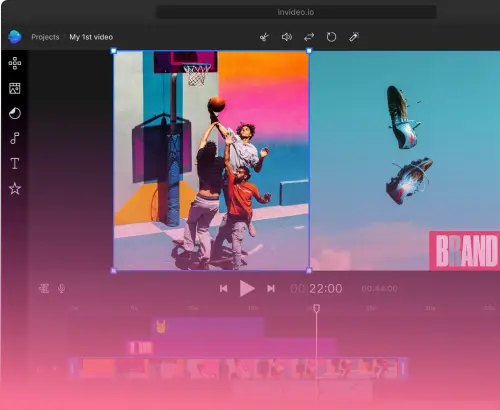

Pro Tip: Instead of working on your entire footage together, you can create a rough cut in parts. Keep your script and narrative handy and begin by working on a few minutes of footage at a time. This will reduce your overall file size and also prevent the editing process from looking like a mammoth task. You can also do this part completely online using an editing tool like InVideo that will help make the process quicker and much more efficient.

3. Recording voice-overs

When recording voice-overs, you need more than just a good quality mic – you need to understand how the mic works, have a space that doesn’t make the sound echo and should also understand voice modulation.

With good quality microphones, you will have a level indicator right within. This helps you see whether the level of the audio is set perfectly. If not, you can invest in an external device that lets you check the audio levels for your audio while it is being recorded. This will save a lot of headache while editing. You want your levels set to peak at roughly -3dB, this gives you enough room for increasing the volume in post without the audio getting distorted.

If you’re not recording the voice in a professional studio, you want to choose a room or setting that is not just bare walls. Pick a room with furniture and other mildly sound absorbing material. Supplement this with foam boards and sound-dampening blankets to get the cleanest audio you can.

Remove distracting sounds from the background if you notice any before you start recording. Also, while you’re recording, don’t fiddle with the mic or keep tapping the table. Do a trial run by recording a few sentences and see if everything sounds good.

Start recording a few seconds before you say the first word and keep recording a few seconds after you speak the last word. As you record, add some expression to your voice. Give it some variation. Smile while speaking where relevant and speak softly where required.

Here are some quick tips you can use as a checklist when you record to make sure the recording is clean and good quality:

Pro Tip: If you have good equipment and a decent place to record audio, you don’t need to spend thousands of dollars investing in audio editors and audio editing software. You can work with something that’s completely online like InVideo – which lets you record voice overs right within the editor, giving you control to trim and cut out parts of it to use in your video.

4. First, second, and third rounds of edits

When learning how to make a documentary, it’s important to understand that you can’t make a documentary with a single edit. There are several rounds of edits that your footage must go through.

When you accept the rough cut as a director, it becomes the first cut of the documentary. However, you can still make changes to it later.

The second cut is where you start focusing on the details of each cut individually – colour grading, rhythm, pacing, adding B-roll and more. The aim of the second cut is to strengthen the documentary’s structure and storytelling.

Finally, you take the documentary to the third cut where the editor starts adding visual effects, voice-overs, and music to the documentary.

Once you’re done with your final round of edits, you want to preview your documentary and also showcase it to other members of the team to iron out any details or flaws you might have missed.

Check out this video by Phil Ebiner on how to edit a documentary to get a better understanding of the process. But keep in mind that this is just one of the many different processes:

5. Make a trailer

Learning how to make a documentary isn’t quite complete until you’ve mastered the art of creating a trailer. Once your documentary is ready, you will want to build up some buzz for it and trailers are one of the best ways to do that. Trailers can help you pique the audience’s interest and promote your documentary on social media.

But first, you need to come up with a story for your trailer so the audience finds it interesting. An ideal way to structure your trailer is with a three-act story. Start the trailer by introducing the documentary’s core idea and relevant characters. The middle of the trailer should show parts of the film that will make the audience curious, and the end of the trailer should be the climax.

Notice how the trailer for The Crime of the Century (2021) follows this structure really well:

The trailer should include the most emotionally tantalizing chunks of the documentary. It’s often easier said than done, but important nonetheless. For instance, if your documentary is about 9/11, show the most terrorizing parts of your film in the trailer.

Voice-overs and sound effects are also important element of a trailer. Trailers are quite short, and some voice-over helps add context and explain the premise more effectively. If you haven’t done a lot of editing before, it may sound overwhelming. However, when you use a beginner-friendly video editor, you’ll be able to add all the bells and whistles to your video with ease.

Step 4: Distributing the Documentary

You’ve come a long way. You’ve invested time into learning how to make a documentary and actually created your masterpiece. Once you’ve created it, you need to send it out to the world. However, there are several options you have in terms of distributing the documentary, such as social media, website, blog, landing pages, and email. Before you start distributing, you should also do some due diligence to see you’re not inviting any legal or copyright issues over.

1. Checking for legal and copyright issues

If you want to distribute your documentary on platforms like Netflix, you’ll need to prove that everything in your documentary is clear of any copyright issues. You’ll need clearances for the following:

- Music

- Script

- Contributors

- Logos of companies

- Products

- Locations

- Anything else that’s copyright-protected

Broadcasters want to avoid legal troubles, so they’ll always need you to prove that there are no copyright issues. Sure, if there are issues, you can often fix them. But finding someone months later and asking them for consent is a hassle and wastes a ton of time.

For this reason, you should always get consent from people you hope to include in your documentary, including people from interviews, with a personal release form. Similarly, you should also get release forms for material (like photographs, artifacts, etc.), groups (like a choir group that appears in your documentary), location, and have your crew members sign a crew deal memo.

In addition to getting permissions and clearances, you should also check the facts stated in the documentary. Inaccuracy can also put you in legal hot waters, so double-check all facts.

2. Different channels of distribution

Now that you’re done with editing your documentary, you need to figure out how to distribute it in order for people to view it. The great thing about documentary filmmaking in 2022 is that you have several different options to distribute your work. We’ve covered seven different ways:

- Self-distribute your documentary online: If you want to distribute your documentary yourself without having to deal with long processes and licensing associated with distribution through larger companies, consider sharing your documentary on social media platforms like YouTube and Vimeo.

- Documentary channels on YouTube: If you feel self-sharing on YouTube won’t get you enough traction, you can partner with channels that are most established on the platform. If they like your documentary, they’ll be willing to share it with their subscribers. Real Stories and DW Documentary examples of channels you can try to approach.

- Streaming sites: You can try pitching your documentary to bigger platforms if you want to put it on a more global stage. You can approach platforms like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon Prime Video for pitching directly, or you may consider going through a film aggregate like Quiver.

- Film festivals: Film festivals can give your documentary a good stage and earn you plenty of recognition, especially if it’s an international film festival. It also gives you the opportunity to network with other filmmakers and Q&A opportunities to grow your knowledge. You can submit your documentary to one of the 10 of the world’s best documentary film festivals to show your artwork to the world.

- Awards: If you believe your documentary stands out, you can submit it to a documentary awards event to give it a badge of honor. Once your documentary has an award, you’ll find it much easier to distribute because you’ll have something to prove your documentary’s value. Consider submitting your documentary to the likes of the Academy Awards (if you’re feeling confident and ambitious), Aurora Awards, and the Peabody Awards.

- Television: You can pitch your documentary to the TV networks just like online platforms. While the process might be a tad lengthier and involve more discussions, having your documentary broadcasted on networks like BBC and HBO will give your documentary a lot of momentum.

- Theatrical release: If a smaller theater is willing to screen the documentary, and your documentary sells out, you can use it as a way to get your documentary screened at a bigger theater.

- DVDs: DVDs are a great way to start earning some income immediately while you’re still working on other distribution channels. Consider selling DVDs of your documentaries at events that align with your story’s subject matter. The events could be held by groups that share a cause similar to the documentary’s message.

Wrapping up

Learning how to make a documentary and creating it requires time and effort. You’ll jump through many hoops to present your thoughts as a story to the world. From figuring out the type of documentary you want to create to making the final edits, you’ll have gone through a rigorous filmmaking experience.

Fortunately, you don’t have to be a film school graduate. You can learn on the go, but it’s always nice to absorb as much information as you can about the process beforehand. Research is perhaps the most challenging aspect of creating a great documentary. However, there are other areas of the documentary-making process that you can simplify to make life easier. For instance, documentaries require extensive editing, which can be difficult if you’re not an editing professional.

While it is best to work with a professional editor to work on your documentary, there are parts of it like trailers, and smaller parts within the documentary that you can perfect on your own using a beginner-friendly video editor. You can edit the documentary yourself even if you don’t have extensive experience using a beginner-friendly video editor. We also share insightful tips on our YouTube channel that you can view for inspiration as you edit your documentary.

This post was written by Arjun and edited by Adete from Team InVideo